The Distributed System ToolKit: Patterns for Composite Containers

Having had the privilege of presenting some ideas from Kubernetes at DockerCon 2015, I thought I would make a blog post to share some of these ideas for those of you who couldn’t be there.

Over the past two years containers have become an increasingly popular way to package and deploy code. Container images solve many real-world problems with existing packaging and deployment tools, but in addition to these significant benefits, containers offer us an opportunity to fundamentally re-think the way we build distributed applications. Just as service oriented architectures (SOA) encouraged the decomposition of applications into modular, focused services, containers should encourage the further decomposition of these services into closely cooperating modular containers. By virtue of establishing a boundary, containers enable users to build their services using modular, reusable components, and this in turn leads to services that are more reliable, more scalable and faster to build than applications built from monolithic containers.

In many ways the switch from VMs to containers is like the switch from monolithic programs of the 1970s and early 80s to modular object-oriented programs of the late 1980s and onward. The abstraction layer provided by the container image has a great deal in common with the abstraction boundary of the class in object-oriented programming, and it allows the same opportunities to improve developer productivity and application quality. Just like the right way to code is the separation of concerns into modular objects, the right way to package applications in containers is the separation of concerns into modular containers. Fundamentally this means breaking up not just the overall application, but also the pieces within any one server into multiple modular containers that are easy to parameterize and re-use. In this way, just like the standard libraries that are ubiquitous in modern languages, most application developers can compose together modular containers that are written by others, and build their applications more quickly and with higher quality components.

The benefits of thinking in terms of modular containers are enormous, in particular, modular containers provide the following:

- Speed application development, since containers can be re-used between teams and even larger communities

- Codify expert knowledge, since everyone collaborates on a single containerized implementation that reflects best-practices rather than a myriad of different home-grown containers with roughly the same functionality

- Enable agile teams, since the container boundary is a natural boundary and contract for team responsibilities

- Provide separation of concerns and focus on specific functionality that reduces spaghetti dependencies and un-testable components

Building an application from modular containers means thinking about symbiotic groups of containers that cooperate to provide a service, not one container per service. In Kubernetes, the embodiment of this modular container service is a Pod. A Pod is a group of containers that share resources like file systems, kernel namespaces and an IP address. The Pod is the atomic unit of scheduling in a Kubernetes cluster, precisely because the symbiotic nature of the containers in the Pod require that they be co-scheduled onto the same machine, and the only way to reliably achieve this is by making container groups atomic scheduling units.

When you start thinking in terms of Pods, there are naturally some general patterns of modular application development that re-occur multiple times. I’m confident that as we move forward in the development of Kubernetes more of these patterns will be identified, but here are three that we see commonly:

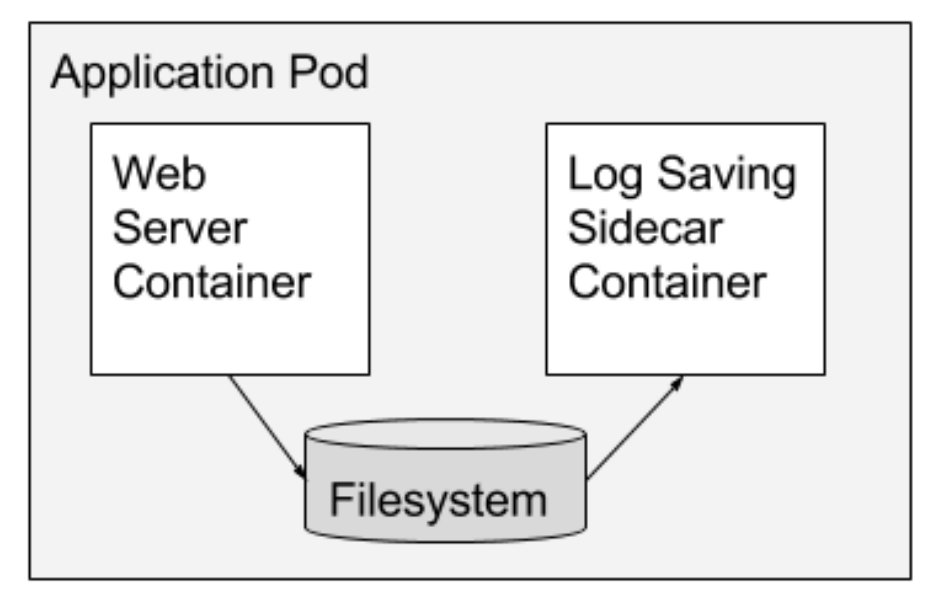

Example #1: Sidecar containers

Sidecar containers extend and enhance the "main" container, they take existing containers and make them better. As an example, consider a container that runs the Nginx web server. Add a different container that syncs the file system with a git repository, share the file system between the containers and you have built Git push-to-deploy. But you’ve done it in a modular manner where the git synchronizer can be built by a different team, and can be reused across many different web servers (Apache, Python, Tomcat, etc). Because of this modularity, you only have to write and test your git synchronizer once and reuse it across numerous apps. And if someone else writes it, you don’t even need to do that.

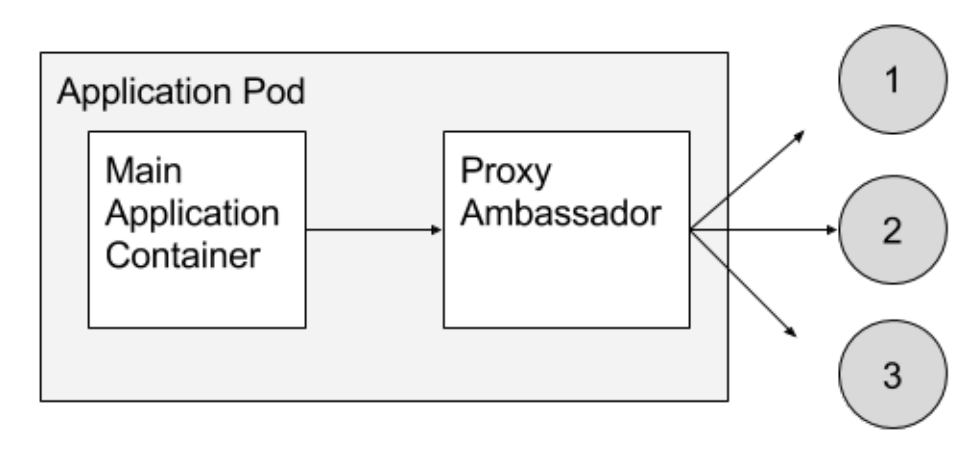

Example #2: Ambassador containers

Ambassador containers proxy a local connection to the world. As an example, consider a Redis cluster with read-replicas and a single write master. You can create a Pod that groups your main application with a Redis ambassador container. The ambassador is a proxy is responsible for splitting reads and writes and sending them on to the appropriate servers. Because these two containers share a network namespace, they share an IP address and your application can open a connection on “localhost” and find the proxy without any service discovery. As far as your main application is concerned, it is simply connecting to a Redis server on localhost. This is powerful, not just because of separation of concerns and the fact that different teams can easily own the components, but also because in the development environment, you can simply skip the proxy and connect directly to a Redis server that is running on localhost.

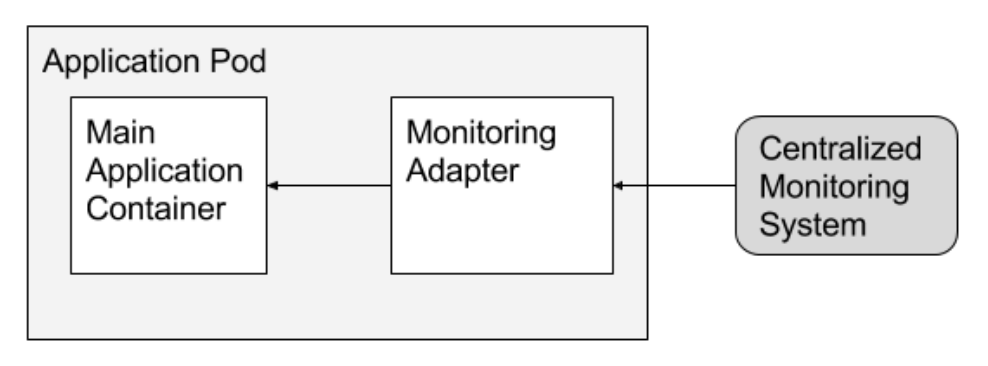

Example #3: Adapter containers

Adapter containers standardize and normalize output. Consider the task of monitoring N different applications. Each application may be built with a different way of exporting monitoring data. (e.g. JMX, StatsD, application specific statistics) but every monitoring system expects a consistent and uniform data model for the monitoring data it collects. By using the adapter pattern of composite containers, you can transform the heterogeneous monitoring data from different systems into a single unified representation by creating Pods that groups the application containers with adapters that know how to do the transformation. Again because these Pods share namespaces and file systems, the coordination of these two containers is simple and straightforward.

In all of these cases, we've used the container boundary as an encapsulation/abstraction boundary that allows us to build modular, reusable components that we combine to build out applications. This reuse enables us to more effectively share containers between different developers, reuse our code across multiple applications, and generally build more reliable, robust distributed systems more quickly. I hope you’ve seen how Pods and composite container patterns can enable you to build robust distributed systems more quickly, and achieve container code re-use. To try these patterns out yourself in your own applications. I encourage you to go check out open source Kubernetes or Google Container Engine.

- Brendan Burns, Software Engineer at Google